One of the earliest memories of life in my native Cuba explains how Caperucita Roja inserted herself into my psyche: I had nine older siblings who took sport in entertaining their littlest sister. One day my brothers built a makeshift, homemade radio and sat me down to listen to their scripted storytelling hour. The storyteller’s voice coming through the box sounded like my oldest brother’s, but to a four year old the inanimate voice was convincing. My brothers never attempted to explain the fairy tale. They simply described the child heroine identical to me and allowed me to draw my own inferences and hang my own projections upon the heroine of the story. It was not until much later I realized they had narrated the fairy tale of “Little Red Riding Hood” while stealthily inserting undeniable details of my personal appearance and personality, making her and me one in my young mind.

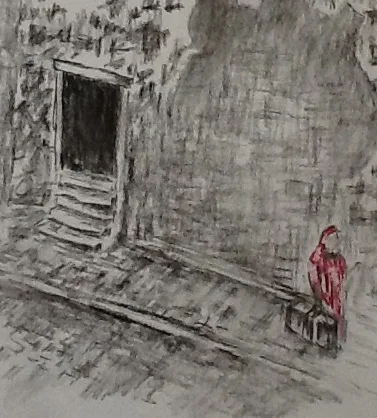

A year later I boarded a plane to America with my Caperucita Roja doll nestled tightly in my arms at the Jose Marti Aeropuerto in Habana. However, she did not make it through the rigorous inspection. I cannot remember much of that rainy traumatic day when I was strip searched by strangers before boarding the plane to America, but I know my Caperucita’s head was snapped off to ensure valuables were not being smuggled inside her body. Afterwards, she was discarded. Carl Jung, the founder of analytical psychology, aptly stated that being exiled or “having no connection with the past is a mutilation of the human being.” This dismemberment of my Caperucita doll is a poignant metaphor for what I and more than 14,000 other Cuban children felt when we fled Cuba without our parents.

Perhaps I write about this in attempts at dismembering the exile complex that has afflicted me all my life. Drawing on the fairy tale of Little Red Riding Hood as a metaphor of my exile experience helps me wrestle with it and bring painful feelings to consciousness. Bruno Bettelheim (1989) in The Uses of Enchantment wrote, “Myths and fairy stories both answer the eternal questions: What is the world really like? How am I to live my life in it?” He suggests, “Recalling how the hero of many a fairy tale succeeded in life… the child believes he may work the same magic” (p. 50). Perhaps by holding tight to Caperucita’s triumph over the Big Bad Wolf, I can also work the same victory in my own life.

I identify with the trauma of having my family and cultural heritage (the symbolic Grandmother) swallowed up by a big, bad wolf. As I write these lines, Fidel Castro’s death is being announced. Though merely a man, to many expelled Cubans he represents the ravenous Big Bad Wolf. Cuban parents risked boarding their 14,000 unaccompanied children on planes to America for fear that Fidel would devour their children with his Leftist agenda. Realizing we could not return to our heritage or our innocent childhood, we were forced into the dark forest and belly of Exile. News reports are attributing Castro’s death to diverticulitis – I would think swallowing up a whole generation of Cuban children would do that to one’s gut! However, as fate would have it, his failed social experiment thrust me into a deep forest (the unconscious) in search of my true inheritance and forced me out of my safe containments to find new life.

In ancient literature, forests represented the edge of civilization. It was impenetrable, wild, uncultivated land, uncontrolled by human or conscious effort. Within it lurked dangerous predators, like hungry wolves or bears, looking to devour their next meal. Hence, the dark forest has long been considered a symbol of the unknown, a metaphor for the unconscious part of the human psyche. The fairy tale forest speaks of a place of testing and even initiation, where something is lost in hopes of something new gained -- the death and rebirth motif. It is there that Caperucita (and all of us) emerge wiser, less innocent, better equipped to face the wolves within, and without.

Caperucita Roja's journey portrays the exile’s rupture from familiar and stable structures; feelings that elicit existential cries within that set the exile on a course to find out who they are, and where, or to whom they belong. This is a fairy tale about death and re-birth, endings and new beginnings. Caperucita Roja reminds me that separation from the comfortable "Mother” and being thrust into dark forests of oppressive containments (e.g. belly of the wolf) can initiate growth and individuation.

Caperucita outsmarted the Big Bad Wolf, Exile, and Death.

...Perhaps so can I!